In the mid-nineteenth century, the state of Illinois was experiencing a financial crisis, and the two political parties—the Whigs and the Democrats—were in constant conflict about how to resolve the issues. In the mix was Lincoln, a Whig lawyer, and then-former legislator and Democratic state auditor James Shields.

In 1842, James Shields, along with the Illinois governor and treasurer, signed an unpopular proclamation that required citizens to pay their taxes and school debts with gold or silver instead of the devalued Illinois bank notes. As you can imagine, the action did not sit well with citizens in possession of little gold or silver. The Whigs saw an opportunity to use the proclamation as a weapon against the Democrats. (Read other posts for more information, beginning with this one)

Between August 19 and September 9, a series of letters addressed to the editor of the Whig paper, Sangamo Journal, from a fictitious farmer’s wife named Aunt Rebecca, pointed an accusatory and defaming finger at James Shields and the Democratic party. The letters were followed by a September 16th poem (related to the Rebecca letters), signed by fictitious Cathleen. The poem and likely two of the Rebecca letters were written by Mary Todd and her friend Julia Jayne. Mary was quite a satirical writer, and she was already very opinionated about politics. Lincoln only admitted to writing the second Rebecca letter, which landed a blow directly at Shields. The letter was a doozy! You can read a transcript of it, in all its colloquial color in the Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln here.

James Shields, then the Illinois state auditor, was MAD, of course! He wrote a letter to Lincoln on September 17, 1842. It was delivered by way of Shields’ friend, John D. Whiteside. The letter is written in formal style with gentlemanly niceties. Until Shields gets to the point. He writes, “I have been the object of slander, vituperation and personal abuse…” He later explains that the editor of the newspaper gave up Lincoln’s name. “I will not take the trouble of enquiring into the reason of all this, but I will take the liberty of requiring full, positive and absolute retraction of all offensive allusions used by you in these communications, in relation to my private character and standing as a man, as an apology for the insults conveyed in them. This may prevent consequences…” That last sentence is a thinly-veiled threat.

As was custom, Lincoln returned a reply that also began with a gentlemanly tone, but he soon landed his own accusatory blow. He writes, “you say you have been informed, through the medium of the editor of the Journal, that I am the author of certain articles in that paper which you deem personally abusive of you: and without stopping to enquire whether I really am the author…”

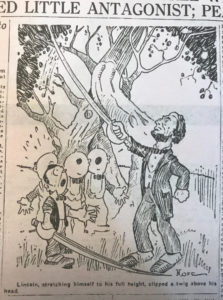

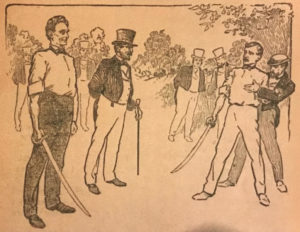

I suspect Lincoln enjoyed wielding this technicality against his political foe. He later admitted only to writing one of the letters, not all of them. He could have simply apologized for the letter he wrote, but he didn’t. Maybe because he would have had to reveal Mary Todd and Julia Jayne’s involvement. Or maybe he was just being stubborn. Whatever the case, Lincoln’s response let Shields know that he didn’t appreciate the assumption. The back-and-forth notes escalated from there until Shields challenged Lincoln to a duel. Lincoln, likely with the counsel of friends, chose broadswords instead of pistols. And he spelled out very unusual terms for the field of honor.

Lincoln’s “second” was Dr. Elias H. Merryman, a military man with duel experience. In fact, many sources imply that Merryman was a fan of dueling and hoped that the Lincoln-Shields fight would proceed. Other Lincoln friends also rushed to Bloody Island, hoping for a peaceful resolution. They included William Butler and Albert T. Bledsoe. James Shields’ second was John D. Whiteside, and his additional friends were Dr. Thomas M. Hope, and Gen. W.D. Ewing.

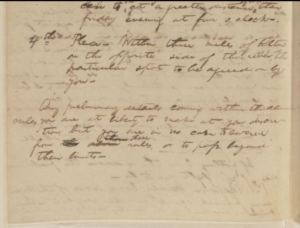

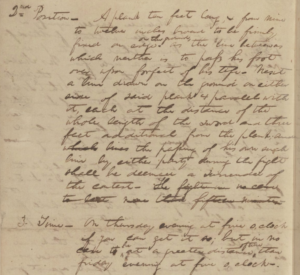

In my book, Abraham Lincoln’s Dueling Words, only two of Lincoln’s dueling terms appear on the page. Below are all four of the terms (with corrected spellings) from Lincoln’s handwritten instructions to Merryman, his second.

1st Weapons — Cavalry broadswords of the largest size precisely equal in all respects — and such as now used by the cavalry company at Jacksonville—

2nd Position — A plank ten feet long, & from nine to twelve inches broad to be firmly fixed on edge — on the ground, as the line between us which neither is to pass his foot over upon forfeit of his life— Next a line drawn on the ground on either side of said plank & parallel with it, each at the distance of the whole length of the sword and three feet additional from the plank; and which lines the passing of his own such line by either party during the fight shall be deemed a surrender of the contest— The fight in no case to last more than fifteen minutes—

3- Time — On Thursday evening at five o’clock if you can get it so; but in no case to be at a greater distance of time than Friday evening at five o’clock—

4th Place — Within three miles of Alton on the opposite side of the river, the particular spot to be agreed on by you—

Any preliminary details coming within the above rules, you are at liberty to make at your discretion; but you are in no case to swerve from the above rules, or to pass beyond their limits—

Above is Lincoln’s letter (incomplete). See the hand-written letter, along with a transcript, at the Library of Congress page here.