In a recent NF kidlit Facebook group, a writer expressed frustration over manuscript feedback that included the terms Theme and Throughline. What does Throughline mean, the writer asked? There was some general head-scratching from responders, along with presumptive definitions that ricocheted in many directions. A couple of us tenured writers had thoughtful responses, but neither of us claimed to be the authority on the subject. The confusion is not surprising. Even in my MFA program, I don’t recall discussions about Throughlines (often spelled Through-lines or Through Lines). The definition, it seems, depends on whom you ask.

In a recent NF kidlit Facebook group, a writer expressed frustration over manuscript feedback that included the terms Theme and Throughline. What does Throughline mean, the writer asked? There was some general head-scratching from responders, along with presumptive definitions that ricocheted in many directions. A couple of us tenured writers had thoughtful responses, but neither of us claimed to be the authority on the subject. The confusion is not surprising. Even in my MFA program, I don’t recall discussions about Throughlines (often spelled Through-lines or Through Lines). The definition, it seems, depends on whom you ask.

It was time to get to the bottom of it, so I scoured the two major storytelling industries—movies and publishing—for more information than any of us needs to grasp the concept of Throughline while marveling at the lack of a unified definition. Only a select handful of sources are included in this post but don’t worry. Since repetition is retention’s glue, I’ve got ya covered. (Also, if you are a graduate student planning to scavenge from this post for your critical work… you’re welcome.)

The Evolution of Throughline/Through-line/Through Line and Why it Matters

(For the purposes of this post, I will use the spelling Throughline)

It appears that the term “Through-line” (note the use of hyphen) was first coined by Russian stage actor and director Constantin Stanislavski at the turn of the 20th century. He believed in a guiding structure that would help actors understand their character’s motivations, goals, desires, objectives. The Stanislavsky system of Objectives was rooted in the belief that every character should have a motivation that inspires them to strive for a goal that sparks decisions that move them closer to the goal in some way—a Super Objective. To Stanislavsky, a Throughline is the invisible thread that keeps the actor on track. The whole point is to create a character that is believable and relatable.

As a concept, Throughline eventually transitioned to screenwriting.

On the blog, Go Into the Story, producer and screenwriter Scott Myers offers this simplification: “Narrative Throughline looks at the screenplay universe as two parts: the External World of Actions and Dialogue, what I [Scott] call the Plotline” and “The Internal World of Intention and Subtext, what I call the Themeline.” In a different post for the same blog, Myers expands on Themeline: “All too often, writers approach theme as an intellectual exercise whereas it works best when we think of a story’s meaning—and specifically its emotional meaning—the various layers of psychological interplay between characters.” In other words, the protagonist’s internal plot is a critical throughline/themeline. In fact, it is the most important. Got it! Reader, before you skip ahead, you might want to check out the blog, Narrative Throughline and genres.

To be clear, not all screenwriters use the term Throughline, but I found it explicitly mentioned in enough screenwriting books and websites to know that the term is alive and well and happily shacked up with its partner term Spine. It is obvious that semantics vary across the industries. Also, it’s relevant to all kinds of narrative, fiction and nonfiction.

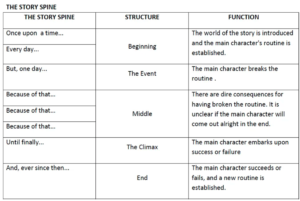

Kenn Adams, acting teacher, author, and Artistic Director of Synergy Theater, takes credit for originating the term Story Spine in 1991, primarily to help Improv actors. You’ll notice in his Story Spine graphic, that he suggests stripping a story down to its “bare-boned structural core…to ensure that the basic building blocks are all in the right place.” Adams points to the omission of character in his Story Spine steps. Completing the story, he implies, comes after the structural Spine.

See clearer Kenn Adams image here https://www.aerogrammestudio.com/2013/06/05/back-to-the-story-spine/

Pixar has embraced Adams’ Story Spine concept, as evidenced by #4 of their viral 22 Rules of Storytelling. During his 2012 TED Talk, Academy-Award-winning Pixar screenwriter Andrew Stanton described how Story Spine was central to the writing of movies like Wall-E, Finding Nemo, Toy Story. The Spine, he says, is the character’s singular subconscious need—an itch they can’t scratch that compels them into every action they take. Stanton’s description puts the character desire front and center.

Pixar has embraced Adams’ Story Spine concept, as evidenced by #4 of their viral 22 Rules of Storytelling. During his 2012 TED Talk, Academy-Award-winning Pixar screenwriter Andrew Stanton described how Story Spine was central to the writing of movies like Wall-E, Finding Nemo, Toy Story. The Spine, he says, is the character’s singular subconscious need—an itch they can’t scratch that compels them into every action they take. Stanton’s description puts the character desire front and center.

In his book, Story: Substance, Structure, Style and Principles of Screenwriting, Robert McKee writes: “The energy of a protagonist’s desire forms the critical element of design known as the Spine of the story (AKA Through-line or Super-objective). The Spine is the deep desire in, and effort by, the protagonist to restore the balance of life.” McKee adds that no matter what, “each scene, image, and word is ultimately an aspect of the Spine, relating, causally or thematically, to this core of desire and action.”

In other words, according to McKee, the Spine is the Super Objective, which is the Throughline, which is the character’s emotional journey and the external journey that must connect to it. (Is your head spinning yet?) There can be separate Throughlines, but the Super Objective refers to the story as a whole.

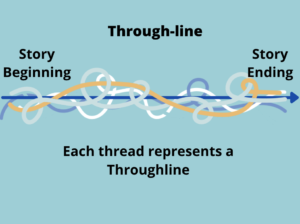

Melanie Anne Phillips, writer, producer, director, and creator of Dramatica, along with her creative partner Chris Huntley, wasn’t aware of Stanislavski’s use of “through-line” before she incorporated “Throughline” into the Dramatica story structure theory in the early 1990s. Phillips defines it as “any elements of a story that have their own beginnings, middles, and ends.” The Overall Story Throughline, she writes, “is the throughline which describes how all of the story’s characters have been brought together. By choosing this Throughline, the author sets the background against which the story will be told.” Dramatica takes it a step further: “There are four throughlines in every story: the Main Character throughline, the Objective Story throughline, the Relationship Story throughline, and the Influence Character throughline. When a story is written, all four of these throughlines are represented in it from beginning to end by the particular events and characters pertaining to each throughline.”

Personally, I twitch at the “every story” declaration, but I do appreciate the consideration for multiple story elements and layers.

(Suddenly, I’m itching to take a screenwriting class)

What do Screenwriting Terms have to do with Writing Books?

What do Screenwriting Terms have to do with Writing Books?

Story is story, so it’s not surprising that the terms Throughline and Spine (less often) migrated into book writing terminology. Currently, they seem to have firmer roots in adult writing than in children’s and YA writing, but I suspect the latter field will soon catch up. Let’s hope a common spelling emerges in the process.

Proof of Spine’s interloping into the writing world can be found in author Steven Pressfield’s great blog post titled “The Spine of the Story,” in which he writes, “What is our Story Spine?… I think of it as ‘Beginning, Middle, End.’ ‘Act One, Act Two, Act Three.’ ‘Hook, Build, Payoff.'” Pressfield agrees with many other modern screenwriters who believe that Spine is first about the narrative structure that can be built upon. As he writes, “What’s the backbone of our story? What narrative architecture supports our tale from beginning to end?” In this example, Spine refers mostly to structure, often described elsewhere as Narrative Throughline.

Isn’t semantics fun? (*cough*)

By contrast, in Beating the Story, Robin D. Laws is in the character-first camp when defining Throughlines, describing it as a structure that reveals character growth. For example, the transformation of a character’s internal arc from innocence to experience, selfishness to altruism, solitude to belonging, guilt to redemption, etc.

Ironically, the best description I found of Throughline in a craft book is from Nancy Lamb in Crafting Stories for Children. “The best way to travel the length of your story is to grab hold of the throughline—the driving force of the book.” That’s a pretty vague statement, but Lamb continues, “some writers think of the throughline as the embodiment of the main character’s conscious desire. The character knows what he wants and knows that he wants it. The personal hunger, shared by the viewer, drives the story and shapes the narrative.” According to Lamb, “when the character’s conscious desire breaks down, either when what she wants is denied or outside circumstances stand in her way, a deeper motivation emerges and propels the character forward.” When this happens, she means, the throughline is replaced with a different throughline that continues the forward momentum like the hand-off in a relay race.

Lest we forget that Throughlines relate to internal AND external threads, Lamb expounds: “Think of a throughline as a locomotive carrying your main character on the journey through your book,” Lamb writes. “You move down the track in one direction only…You always maintain a forward-moving trajectory…You might change tracks, but you don’t bring the throughline to a halt before it connects to the next throughline or reaches the final destination.”

That makes sense, yes? But my curiosity about various other kinds of Throughlines is still piqued.

The protagonist faces challenges while in pursuit of their goal, usually evolving in some way (and growing the story theme) by the story’s end.

The Various Kinds of Throughlines

I stumbled onto New York Times bestselling author Chuck Wendig’s blog post titled “Shot Through the Heart: Your Story’s Throughline,” and found myself both giggling and face-palming with an audible “duh!” If you choose to skip the other scholars and book nerds of the world, don’t miss Wendig’s description of Throughline. His conversational style, laced with adult snarkiness and glorious simplicity, is refreshing. Ignore the F-bombs and enjoy the pragmatic examples of how a Throughline can be built from anything, including your story theme, a character trait, internal plot, external plot, a motif, recurring metaphors or refrains, mood, language, etc. As Wendig writes, “a throughline is any element you can carry through the entire story and can be internal or external or both.” Wendig goes on to explain that the story’s primary Throughline is “the invisible thread that binds your story together. It comprises those elements that are critical to the very heart of your tale.”

To summarize: A Throughline is an element of your story that is stitched like a needle and thread through your narrative. Within the screenwriting and book writing industries, there are enough nuanced definitions to make your head spin, until you step back and realize the mutual messages: the protagonist’s desire line and motivation must be consistent and ever-present. The character IS the story, while the external plot of cause-and-effect-based scenes unfold and spark the character to act in some way. Ultimately, the character’s journey reveals the story theme. For the story to be cohesive, the most important elements must weave through the narrative like so many threads.

We stitch stories together with colored, ashen, textured, smooth, frozen, blazing, fragile, fraying, threads until, together, they create complete scenes that logically connect, allowing the character and her ordeal to reveal a golden thread of truth that changes her and connects to the reader’s heart.

If you’ve read this far, especially if you’ve followed the links to fuller articles, you should have a solid grasp of what a Throughline is, even without a single unified description. Remember that some people will use Throughline to mean structure, emotional plot, narrative plot, theme. If you receive manuscript feedback that points to your Throughline without context, ask for clarification.

Identify the primary Throughlines in your Manuscript (simplified)

Protagonist’s Emotional Throughline: Are you consistent with your protagonist’s desire, motivation, and character traits, while allowing her flaw, weakness, or inner turmoil (selfishness, fear, loneliness, trauma, poverty, homelessness, move to a new school, loss of friend, etc.) to be ever-present, even in the background? As she pursues a goal (voluntary or involuntary) does she face obstacles? Does she reach her original goal, or does she emerge with what she didn’t know she needed? Remember that a character’s goal can change but it must be logical. Does the character’s ordeal reveal the overall story theme?

Narrative Throughline: The focused external plot (stuff that happens) in which every scene emerges from the character’s desire and actions. Have you structured your tale with cause-and-effect action? Do your scenes connect logically?

Themeline: What is the story is about? In other words, what is the lesson or moral that emerges organically from your character’s ordeal? Without a theme, you will have plodding events, even spectacular epic events, but no reason for anyone to really care about them. The theme is a universal human truth(s).

Mini-Throughlines: If you use a metaphor, a refrain, a motif, a narrator, a specific voice, a mood, humor, a pattern, think of them each as a needle with thread. Make sure you stitch them all the way through your story.

Subplot Throughlines: Whether it’s a secondary character or an external force (weather, war, impending event, etc.), make sure not to leave these elements dangling. Give them the appropriate amount of presence, agency, and resolution.

I hope you find this post more helpful than dizzying. Whether or not you choose to use the term Throughline is a personal choice. But if you’re ever at a book nerd cocktail party, or in a social media conversation, you’ll be able to skip the confused head-scratching and speak up like a boss.

Happy writing!

P.S.) The more complex your narrative and form, the greater potential for multiple Throughlines and mini-Throughlines. The reverse is true for short and simple stories. A short narrative picture book might have one narrative Throughline, one Emotional/Character Throughline, one Theme, one visual motif. A concept picture book will be a different creature altogether.

Thanks for this brilliant analysis, Donna! The rare occasions I’ve used “throughline, ” it was synonymously with Candy Fleming’s “core idea” definitely. Next time it comes up, I’ll refer people to this post! I love your advice for people to ask for clarification if they get that as part of the feedback on their stories.

Wow, this is terrific, Donna. I absolutely love your colorful description of story-stitching. I’m going to clip that one. I kind of think of it as the melodic melody that weaves through a symphony. Your guide to identifying Throughlines comes in handy as I do round 3 revisions of my completed MG novel.